Sunday, September 3, 2023

The art difference are the mummy's coffins

Why did Egyptian artists create statues that look straight ahead?

because they were designed to face the ritual being performed before them.

Ancient Egyptian art

Appreciating & understanding ancient Egyptian art

Art not meant to be seen

The function of Egyptian art

What we see in museums

Modes of representation for three-dimensional art

Modes of representation for two-dimensional art

Registers

Hierarchy of scale

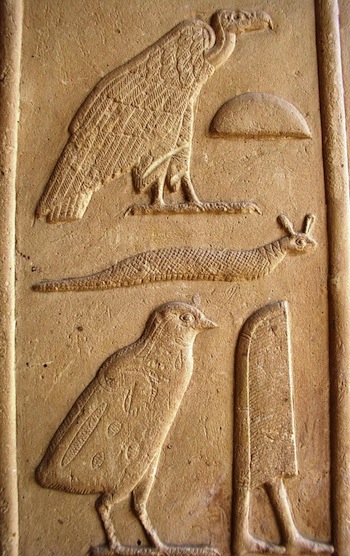

Text and image

De gebroken neuzen van Egypte - Egypt's broken noses

Waarom hebben zoveel Egyptische beelden een gebroken neus?

Julia Wolkoff

Bijgewerkt om 22:24 EDT, woensdag 20 maart 2019

Editor’s Note: This article was published in partnership with Artsy, the global platform for discovering and collecting art. The original article can be seen here.

see the original english text on CNN

De meest voorkomende vraag die curator Edward Bleiberg stelt van bezoekers aan de Egyptische kunstgalerijen van het Brooklyn Museum is een eenvoudige maar opvallende vraag: waarom zijn de neuzen van de beelden gebroken?

Het lijkt misschien onvermijdelijk dat een eeuwenoud artefact na duizenden jaren slijtage vertoont. Maar deze simpele observatie bracht Bleiberg ertoe een wijdverbreid patroon van opzettelijke vernietiging bloot te leggen, dat wees op een complexe reeks redenen waarom de meeste Egyptische kunstwerken überhaupt werden beschadigd.

Bleibergs onderzoek vormt nu de basis van de aangrijpende tentoonstelling ‘Striking Power: Iconoclasm in Ancient Egypt ’.

Een selectie objecten uit de collectie van het Brooklyn Museum reist later deze maand naar de Pulitzer Arts Foundation onder co-directie van diens associate curator, Stephanie Weissberg. Door beschadigde beelden en reliëfs uit de 25e eeuw voor Christus tot de 1e eeuw na Christus te combineren met intacte tegenhangers, getuigt de tentoonstelling van de politieke en religieuze functies van oude Egyptische artefacten – en van de diepgewortelde cultuur van het iconoclasme die tot hun verminking leidde.

Egypte haalt gestolen eeuwenoude artefacten terug van een Londense veiling

In ons eigen tijdperk waarin rekening wordt gehouden met nationale monumenten en andere openbare kunstuitingen, voegt ‘Striking Power’ een relevante dimensie toe aan ons begrip van een van ‘s werelds oudste en langstlevende beschavingen, waarvan de visuele cultuur voor het grootste deel onveranderd bleef. gedurende millennia. Deze stilistische continuïteit weerspiegelt – en draagt rechtstreeks bij aan – de langdurige stabiliteit van het rijk. Maar invasies door krachten van buitenaf, machtsstrijd tussen dynastieke heersers en andere perioden van onrust lieten hun littekens achter.

"De consistentie van de patronen waarin schade wordt aangetroffen in de beeldhouwkunst suggereert dat het doelbewust is," zei Bleiberg, daarbij verwijzend naar talloze politieke, religieuze, persoonlijke en criminele motivaties voor daden van vandalisme. Het onderscheiden van het verschil tussen accidentele schade en opzettelijk vandalisme kwam neer op het herkennen van dergelijke patronen. Een uitstekende neus op een driedimensionaal beeld is gemakkelijk kapot te maken, gaf hij toe, maar de plot wordt dikker als platte reliëfs ook gebroken neuzen vertonen.

Platte reliëfs vertonen vaak ook beschadigde neuzen, wat het idee ondersteunt dat het vandalisme het doelwit was.Brooklyn-museum

Het is belangrijk op te merken dat de oude Egyptenaren belangrijke krachten toeschreven aan afbeeldingen van de menselijke vorm. Ze geloofden dat de essentie van een godheid een beeld van die godheid kon bewonen, of, in het geval van gewone stervelingen, een deel van de ziel van die overleden mens een standbeeld kon bewonen dat voor die specifieke persoon was ingeschreven. Deze vandalismecampagnes waren daarom bedoeld om “de kracht van een beeld te deactiveren”, zoals Bleiberg het uitdrukte.

Het teruggeven van geroofde artefacten zal uiteindelijk het erfgoed herstellen van de briljante culturen die ze hebben gemaakt

Graven en tempels waren de bewaarplaatsen voor de meeste sculpturen en reliëfs die een ritueel doel hadden. “Ze hebben allemaal te maken met de economie van offers aan het bovennatuurlijke”, zei Bleiberg. In een tombe dienden ze om de overledene in de volgende wereld te ‘voeden’ met voedselgeschenken uit deze wereld. In tempels worden afbeeldingen van goden getoond die offers ontvangen van afbeeldingen van koningen of andere elites die een standbeeld kunnen laten maken.

‘De Egyptische staatsreligie’, legde Bleiberg uit, werd gezien als ‘een regeling waarbij koningen op aarde voor de godheid zorgen, en in ruil daarvoor zorgt de godheid voor Egypte.’ Beelden en reliëfs waren ‘een ontmoetingspunt tussen het bovennatuurlijke en deze wereld’, zei hij, en werden pas bewoond of ‘nieuw leven ingeblazen’ wanneer het ritueel werd uitgevoerd. En beeldenstormen zouden die macht kunnen ontwrichten.

“Het beschadigde deel van het lichaam kan zijn werk niet meer doen”, legt Bleiberg uit. Zonder neus houdt de beeldgeest op met ademen, zodat de vandaal hem feitelijk ‘doodt’. Het afslaan van de oren van een beeld van een god zou ervoor zorgen dat het een gebed niet meer kan horen. Bij beelden die bedoeld zijn om mensen te laten zien die offers brengen aan goden, wordt de linkerarm – die meestal wordt gebruikt om offers te brengen – afgesneden, zodat de functie van het beeld niet kan worden uitgeoefend (de rechterhand wordt vaak met een bijl aangetroffen bij beelden die offers ontvangen).

'Gods in Color' geeft oudheden terug in hun oorspronkelijke, kleurrijke grandeur

“In de faraonische periode bestond er een duidelijk begrip van wat beeldhouwkunst moest doen,” zei Bleiberg. Ook al was een kleine grafrover vooral geïnteresseerd in het stelen van de kostbare voorwerpen, hij was ook bezorgd dat de overledene wraak zou nemen als zijn weergegeven gelijkenis niet zou worden verminkt.

De heersende praktijk van het beschadigen van beelden van de menselijke vorm – en de angst rond de ontheiliging – dateert uit het begin van de Egyptische geschiedenis. Opzettelijk beschadigde mummies uit de prehistorie spreken bijvoorbeeld van een ‘zeer fundamentele culturele overtuiging dat het beschadigen van het beeld de afgebeelde persoon schaadt’, zei Bleiberg. Op dezelfde manier gaven how-to-hiërogliefen instructies voor krijgers die op het punt stonden de strijd aan te gaan: maak een wassen beeld van de vijand en vernietig deze. Een reeks teksten beschrijft de angst dat je eigen imago beschadigd raakt, en farao's vaardigden regelmatig decreten uit met vreselijke straffen voor iedereen die hun gelijkenis zou durven bedreigen.

Een standbeeld uit ongeveer 1353-1336 v.Chr., Met een deel van het gezicht van een koningin.Het Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

‘Beeldenstorm op grote schaal…was vooral politiek van motief’, schrijft Bleiberg in de tentoonstellingscatalogus voor ‘Striking Power’. Het bekladden van standbeelden hielp ambitieuze heersers (en toekomstige heersers) de geschiedenis in hun voordeel te herschrijven. Door de eeuwen heen vond deze uitwissing vaak plaats langs gendergerelateerde lijnen: de erfenis van twee machtige Egyptische koninginnen wier autoriteit en mystiek de culturele verbeelding voeden – Hatsjepsoet en Nefertiti – werden grotendeels uit de beeldcultuur gewist.

Archeologen ontdekken een dorp in Egypte dat ouder is dan de farao's

“De regering van Hatsjepsoet vormde een probleem voor de legitimiteit van de opvolger van Thoetmosis III, en Thoetmosis loste dit probleem op door vrijwel alle imaginaire en ingeschreven herinneringen aan Hatsjepsoet te elimineren”, schrijft Bleiberg. Nefertiti's echtgenoot Achnaton zorgde tijdens zijn religieuze revolutie in de Amarna-periode (ca. 1353-36 v.Chr.) voor een zeldzame stilistische verschuiving in de Egyptische kunst. De opeenvolgende opstanden van zijn zoon Toetanchamon en zijn soortgenoten omvatten onder meer het herstel van de oude aanbidding van de god Amon; “de vernietiging van de monumenten van Achnaton was daarom grondig en effectief”, schrijft Bleiberg. Toch leden ook Nefertiti en haar dochters; deze beeldenstorm heeft veel details van haar regering verdoezeld.

De oude Egyptenaren namen maatregelen om hun sculpturen te beschermen. Beelden werden in nissen in graven of tempels geplaatst om ze aan drie zijden te beschermen. Ze zouden achter een muur worden vastgezet, met hun ogen op één lijn met twee gaten, waarvoor een priester zijn offer zou brengen. ‘Ze hebben gedaan wat ze konden’, zei Bleiberg. “Het werkte eigenlijk niet zo goed.”

Een standbeeld van de Egyptische koningin Hatsjepsoet met een "qat" -hoofdtooi.Het Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Speaking to the futility of such measures, Bleiberg appraised the skill evidenced by the iconoclasts. “They were not vandals,” he clarified. “They were not recklessly and randomly striking out works of art.” In fact, the targeted precision of their chisels suggests that they were skilled laborers, trained and hired for this exact purpose. “Often in the Pharaonic period,” Bleiberg said, “it’s really only the name of the person who is targeted, in the inscription. This means that the person doing the damage could read!”

Archaeologists unearth a mysterious sarcophagus in Egypt

The understanding of these statues changed over time as cultural mores shifted. In the early Christian period in Egypt, between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD, the indigenous gods inhabiting the sculptures were feared as pagan demons; to dismantle paganism, its ritual tools – especially statues making offerings – were attacked. After the Muslim invasion in the 7th century, scholars surmise, Egyptians had lost any fear of these ancient ritual objects. During this time, stone statues were regularly trimmed into rectangles and used as building blocks in construction projects.

“Ancient temples were somewhat seen as quarries,” Bleiberg said, noting that “when you walk around medieval Cairo, you can see a much more ancient Egyptian object built into a wall.”

Statue of pharaoh Senwosret III, who ruled in the 2nd century BCThe Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Such a practice seems especially outrageous to modern viewers, considering our appreciation of Egyptian artifacts as masterful works of fine art, but Bleiberg is quick to point out that “ancient Egyptians didn’t have a word for ‘art.’ They would have referred to these objects as ‘equipment.’” When we talk about these artifacts as works of art, he said, we de-contextualize them. Still, these ideas about the power of images are not peculiar to the ancient world, he observed, referring to our own age of questioning cultural patrimony and public monuments.

“Beeldspraak in de openbare ruimte is een weerspiegeling van wie de macht heeft om het verhaal te vertellen van wat er is gebeurd en wat herinnerd moet worden”, aldus Bleiberg. “We zijn getuige van de empowerment van veel groepen mensen met verschillende meningen over wat het juiste verhaal is.” Misschien kunnen we leren van de farao's; De manier waarop we ervoor kiezen om onze nationale verhalen te herschrijven vergt wellicht slechts een paar daden van iconoclasme.

‘ Striking Power: Iconoclasm in Ancient Egypt ’ is te zien bij de Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis, Missouri, van 22 maart tot 11 augustus 2019.

-

The boy worker who brought a boy King back to life On that day from hundred years ago, there was a boy who should have been playing like the...

-

Napoleon Bonaparte's campaign in the Ottoman territories of Egypt and Syria, proclaimed to defend French trade interests and to establ...

-

When Howard Carter found the tomb of the boy king Tutankhamun in 1922, he also found the remains of two foetuses buried in the pharaoh...